Friends of our now defunct Ring community, it is time to take stock, but even more so to think fundamentally.

What should a DAO be in order to serve the initial purpose for which it was imagined ?

If the solutions proposed by the different protocols of DeFi or the NFT community seem at first sight to work correctly, when we go deeper into the subject, we quickly realize that they are far from meeting the requirements of representativeness and decentralization which seems desirable for a DAO. But besides, power by the Holders and for the Holders, to what extent is it really a good idea? Let’s try to decipher the problems that governance must face.

- 1/ Observation: First governance vote of the xExchange

- 2/ A few quick reminders about DAO

- 3/ The different types of governance

- 4/ But what exactly should we govern?

- 5/ The crucial importance of the mathematical function of voting power

- 6/ How to choose the most suitable ballot for a DAO

- 7/ Governance according to the Game Theory

- 8/ Governance risks

- 9/ Summary of the essential characteristics of a DAO imo

- 10/ Conclusion

1/ Observation: First governance vote of the xExchange

Official result of the first vote

The result is unequivocal: the transition to MEX 2.0 is approved by the DAO by more than 88%, with more than 60% participation, a statistic that is actually underestimated, but I will come back to this later.

Difference in results depending on how voting power is considered

15013 accounts participated in the vote, 13959 accounts voted for MEX 2.0, 700 against, and 354 abstained. Comparing the two graphs, we can see that the voting power has over-represented the share of “No” and “Abstain” votes. If we were in a democracy, the proposal would have been voted at almost 93%, which shows a very significant representativeness of the vote despite the very unequal voting power between the participants, rather reassuring, for this time.

Because yes, to be unequal, it is very unequal. Take a look at the ranking of the 40 most powerful accounts and their share of the total voting power.

Top 40 biggest voters in the first vote

Below is the logarithmic scale curve of the distribution of voting power according to LKMEX Top Holder. The most powerful wallet has 8.7% of the voting power. The top 10 has 32%, the top 500 has 77.6%.

Distribution of cumulative voting power according to the ranking of the largest voters (logarythmic)

The imbalance is even more obvious when we look at this distribution in linear scale.

Distribution of cumulative voting power according to the ranking of the largest voters (linear)

The majority is held by… only 34 accounts. That’s 0.22% of the total number of participants holding just over 2 trillion LKMEX.

As for the percentage of participation, it is for me largely underestimated because it is calculated on the total supply of MEX which is 6859 billions, however, all the MEX are not locked in LKMEX, 974 billions of MEX are still in the wallets of the team, 106 billions in the form of MEX in the pool EGLD<>MEX and about 475 billions held by the various smart-contract and wallets of the users, which would give us at minimum 77% of participation. In the darkest phase of the bear market, I don’t know about you, but I find this huge, proof of the resilience of the MultiversX ecosystem users!

But it is not because this vote is rather representative of the general opinion, that it will always be, that is why it is very important to keep in mind that the distribution of the power of vote will surely pose more problem in the future, although this one will be subject to modification with the arrival of xMEX, the power of vote of each one being able to be multiplied up to 4 times thanks to the energy feature.

We will discuss below the possible improvements to be implemented in order to increase the decentralization of the voting power, its representativeness but also the relevance of such a change.

Let’s move on to the real subject of this article, how a DAO should govern and what issues it should overcome.

2/ A few quick reminders about DAO

A Decentralized Autonomous Organization is an entity composed of several stakeholders involved in its action and evolution, in the framework of MultiversX and the xExchange this represents all the people holding xMEX. It operates through decentralized technologies — in this case the MultiversX Blockchain — and its voting infrastructure is governed by rules written in Smarts Contracts.

But we have greatly misused the D of DAO. Decentralization does not originally refer directly to the degree of decentralization of decisions or voting power — although desirable — but to the structural decentralization of the means by which this DAO exists via the code and the blockchain, allowing transparency, incorruptibility, and immutability of the governance system. Therefore, it is not because the voting power is held by a handful of Holders that a DAO loses its decentralized character.

This is why in the end most DAOs are not decentralized democracies, but rather similar to corporate boards where you have voting power indexed to your shares in the company or to plutocratic regimes where your wealth represents your voting power.

In order not to break the initial vision, ideal and popular of the DAO, but especially to define its intrinsic functioning, it is important according to me to ask the question of the power of vote, of who must hold it, of the type of ballot to be used but also to understand the workings and the problems of the governance in general

3/ The different types of governance

There are as many types of governance as there are entities to be governed, whether they are community, corporate, or nation-wide. Each governance mechanism must be adapted to what it has to govern. We can distinguish three main types:

- Centralized governance

- Hybrid governance

- Decentralized governance

Centralized governance

Logically, we will find centralized governments, dictatorships, absolute monarchies, non-capitalized corporate boards, and more. The three regal powers — legislative, executive and judicial — are centralized around one or more persons with common interests. Moreover, the operations of such entities are usually completely opaque.

Hybrid governance

For hybrid governments, we could include all our modern democracies and parliamentary monarchies, each with different degrees of centralization and decentralization according to their intrinsic mechanisms of governance and operation. In France, for example, the three categories of power, executive, legislative and judicial, are decentralized, which is what we call the separation of powers. We elect by direct universal suffrage our President who is responsible for building a government composed of ministers who propose laws and are responsible for implementing them. We elect by a decentralized and democratic voting power the person who will centralize the executive power, it is a kind of representative centralization (well, it tries to be). The functioning of these entities remains relatively decentralized, but when we talk about corruption, transparency, representativeness or access to political life, we come across generally less glorious findings.

Decentralized governance

For decentralized governance, I would only include entities whose functioning is totally decentralized and where all stakeholders actively participate in each decision. Therefore, apart from our famous DAO, there are very few examples in “real life” that could fit into this framework, some of them are close to it, such as the “Landsgemeinde” in Switzerland, a historical governance where the three regalian powers were given to the people and voted in popular assemblies. Switzerland is probably one of the countries where governance and the different state powers are the most decentralized in the world.

Then you can further subdivide all these systems according to which stakeholders hold the power, directly or via voting. Some non-random examples:

- Democraty (power to the people),

- Plutocraty (power to the richest),

- Networkcraty (power to the member of a network),

- Adhocracy (power to multidisciplinary and specialized organizations),

- Meritocraty (power to the most deserving)

- Epistemocracy (power to the most knowledgeable).

For example, for its first vote, the governance of the xExchange was a mix of networkcracy and plutocracy, each one having a voting power in relation with its monetary commitment, but also received at the beginning according to the intensity of its participation in the Elrond blockchain via stacking.

A DAO, especially for a decentralized exchange, is a bit of a peculiar governance because it is somewhere between a corporate board where only the biggest investors have a right of governance, and a community governance where all its members can participate. In my opinion, it should neither be governed like a corporate board because unlike those, we do not receive dividends per share, but use a real micro-economy, we all have different interests, different investor profiles and different portfolios, nor like a country for example, which gives equal voting power to each of its citizens. This is the reason why I say that a governance indexed linearly and only on the size of our wallet is not the most appropriate choice.

I personally think that the ultimate DAO is a clever mix of all the above characteristics in order to have an equitable (which does not mean egalitarian) decision making power according to their importance in the ecosystem.

We could imagine a governance that would give X% of voting power to a multidisciplinary board of experts elected by the community, X% to the validators of the Blockchain, X% to the Y wallets with the most xMEX, X% to the Y most deserving users in relation to their activities on the Dex, and X% to all users who do not fit into one of these categories. Then our voting power to each would be indexed according to the amount of xMEX we hold relative to the group we belong to.

This allowed us to index our voting power not only to our monetary commitment to the xExchange, but to all kinds of contributions.

With these few lines, it is clear that governance and its decentralization remain very broad themes, so it is necessary to define what a DAO should govern and which aspects of governance should be centralized or decentralized in order to have the best efficiency and representativeness adapted to its functioning.

4/ But what exactly should we govern?

With the above examples of governance types, it is clear that the degree of centralization is not binary, but linear, and depends on many factors; each governance entity enjoys a certain degree of centralization or decentralization.

This is for schematic purposes only, Kim, don’t nuke my house pls

Where would you place a DAO on this frieze? Its construction is centralized around the founders/builder of the project and is progressively decentralized, especially around decisions that have a lot of impact on the community, but often the voting power is extremely centralized compared to a democracy with direct universal voting. On the other hand, its intrinsic functioning is completely decentralized through the use of smart contracts and transparent thanks to the blockchain.

Not so obvious, eh? Surely it would be better to represent this frieze as the sum of the components that can be subject to centralization.

Always for schematic purposes only, don’t take positions too seriously

This would already be a more accurate and detailed vision of how to characterize the centralization of a governance, there would be an incalculable number of parameters, each of which could be further subdivided and not all of them comparable between different entities. (Even if I tried to make the different positioning logical, again it is very schematic, do not take it as objective findings)

All this to bring you to a question about the governance of the xExchange:

Decentralization, yes, but for what?

Implementing full decentralization of DEX development with a hundred million dollar TVL like the xExchange would be very complicated and risky. Collaborative development linked to community governance can make it either slow or chaotic and introduces the risk of adding malicious code, it could be unmanageable. Although risky, it is probably possible if a platform is built initially for this purpose, but it is a bit too degen to implement in an existing DEX in my opinion. Every component of governance would have to be robust to all sorts of manipulation, and it would not be ethical to expose all users to that kind of risk. But if some people want to try to develop this kind of platform, good luck, it’s quite a challenge!

In the context of the xExchange, governance should initially be used to receive feedback from the community on improvements made and new features, those it considers most important to implement in the short term, to allow it to propose improvements, to vote on the pools that should receive the most APR, to vote on the projects to be included in the DEX from a shortlist established by the Core Team or proposed by the community itself, and many more.

Before thinking about any possibility of collaborative development, it is necessary to succeed in building a successful and non-manipulable decentralization of the governance itself. Whether it is about the mathematical function that should govern the power of vote, about which ballot to choose for each type of vote in order to make them fair for the community, to allow incentives that favor decentralization rather than the “plutocratic” system by which most DAOs are submitted, etc.

At the moment, this is the kind of discussion we need to have, not that of making governance all-powerful to the point of extracting all the power of initiative and development from the Core Team.

We need to define the framework of influence as well as the governance actors within the xExchange, in order to create a system that provides real added value.

I will try to define some categories/classes of votes, it will certainly not be exhaustive, but will allow to put a foot in the subject:

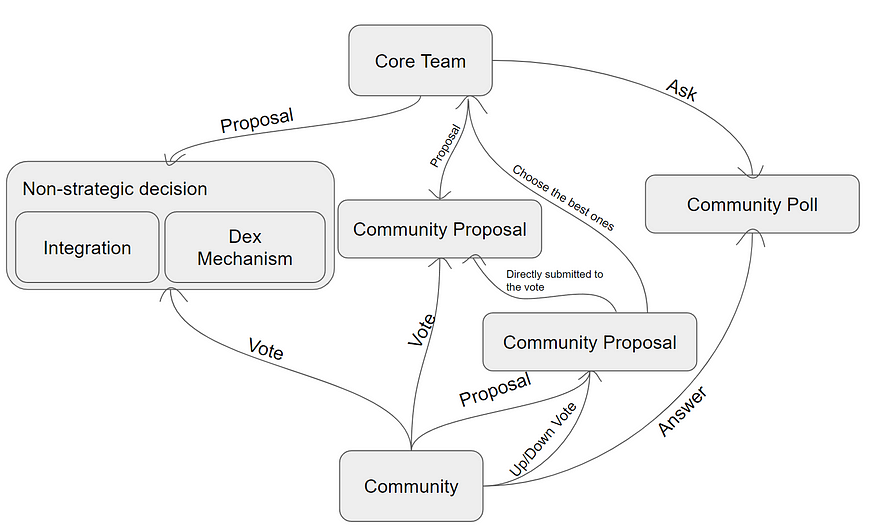

Graph of interactions between the community and the team

I see three main families of interactions between the Core Team and the community:

- Votes on non-strategic decisions, this would include all votes allowing for example, the integration of new tokens on the Dex, in the Metabounding, Metastacking, adding new farming pools, etc.. But also votes about the different DeFi mechanisms of the xExchange like the vote about the switch to MEX 2.0, future votes about which pools to favor for farming rewards, the vote that should happen in 7 years about MEX inflation, the possibility to change the fees, etc.

- A mechanism to allow the emergence of proposals by community, we could imagine an open proposal system with an up and down vote system to give visibility to the best of them (or the use of another ballot that I present later in the article), the Core Team or an elected community of experts could then choose the most relevant ones to submit to the vote. One can also imagine a direct vote for the proposals that would meet certain requirements of popularity and representativeness in order to bypass centralized decisions when they are not necessary to avoid any abuse of power.

- Finally, a community survey system, allowing the Core Team (or the community itself) to know the community’s opinion on various subjects in order to act in consultation.

Again, I repeat, this is not exhaustive and it will be important to discuss in the community, besides, a forum present on the Dex seems essential to animate these discussions and push the community to get involved in these topics. And as already stated earlier, I personally think that an expert council can be very useful to make the link between the Core Team and the community, for example to choose which proposals are interesting to submit to the vote, to be able to prepare explanatory content of the latest updates before they are announced, to animate the fundamental discussions around the votes and the governance itself, etc.

5/ The crucial importance of the mathematical function of voting power

As seen in points 1 and 3, it is not because there is a vote, that this one allows, in a certain way, a representativeness of the results worthy of the name. The share of vote that a system chooses to give to its different voters irremediably influences the regime to which it will belong. For its first vote, MultiversX chose simplicity, 1 LKMEX = 1 vote, making the governance “plutocratic”, the more LKMEX you have, the more voting power you have. But this is temporary, because now that the xMEX implementation is accepted by the community, we will move to 1 vote = 1 energy. It will therefore be possible to multiply your voting power by a factor of 1 to 4, adding a dimension of time commitment to the voting power.

The resulting distribution will depend on the choice that each wallet will make on its long-term commitment in this famous token, which will certainly allow the smallest holder to gain a few points of power over the Whales, but probably not enough to reverse the mathematical distribution of the latter.

In the best case, if we imagine that the TOP 34 wallets — which enjoys the majority — does not want to give energy to their xMEX, while the remaining 50% percent of voting power lock them in for 4 years, the risk of a deal between these accounts to manipulate the vote for sure in their favor would already be diminished and would require almost 10 times more participants in this deal.

Distribution of voting power if it is considered that the majority held by top 34 holder has not locked these xMEX

According to this distribution of voting power, the Top 420 wallets would have to band together to hold the majority — that is 2.8% of the total participants — the vote would remain weakly representative of all voters and important contributors. As the very large wallets and the others do not necessarily have the same interests in the xExchange, it is important to try to keep the representation rate high enough.

To do this, it is necessary to change the mathematical function governing the voting power. A good alternative to the so-called linear voting power (1 energy = 1 vote) is to use a Root function √x where x represents your voting power.

Cumulative distribution of voting power according to square root and cubic functions

In red, the actual distribution, in blue, the distribution according to a square root function, in green, the distribution according to a cube root function. We can see the mitigating effect, especially for the first 500 accounts. So that’s it? Everything is set? Unfortunately, it is more complicated than that.

If the function fulfills its… function well, to decrease the power of the biggest Holder, it also reduces the impact of the average wallet in favor of the smallest accounts. The problem is that this kind of distribution makes governance fallible on one point.

The Sybil attack.

A Sybil attack is the use of a large number of false accounts, false identities, in order to multiply its power within a reputation system. Exactly what we saw during Launchpad to increase the chances of winning lottery tickets. Therefore, if we want to decrease the power of very large wallets, we must also make sure that it is not too easy to gain power through the multiplication of small accounts.

The ideal distribution according to me and only according to me (in y the cumulative % of voting power, in x the % of total voters)

A distribution that I would personally find well constructed (taking into account that xMex are not transferable and if it were to be indexed only to our monetary power) would look something like this, the Top 10% Holder would have 20% of the voting power (vs. 88% at present), the Top 10–20% would have 30% of the power (vs. 5.5%), the Top 20–40% would have 30% (vs. 3.3%) and the Top +40% would have 20% (vs. 2.2%). I deliberately gave more power to the Top 10–20% category than to the Top 10%, so that a decision, if it is to be accepted via the voting power of the biggest wallets, must necessarily be fully approved by the “average” wallets, reducing the possibility that a decision benefiting the very big Holders to the detriment of the others could not be accepted.

This would allow for a real political game between the different categories of Holder, increase the interest in energizing our xMEX for all stakeholders, be relatively resilient to Sybil attacks (the smallest 20% of accounts would only have 1.5% of the voting power), and have increased representativeness without taking power away from the people who are most engaged and important within the network.

Building a distribution that meets all these needs is not easy, knowing that it will be subject to variation according to the commitment of each person to energy. But it is a model that we can surely try to approach!

6/ How to choose the most suitable ballot for a DAO

In any voting system, the ballot is something crucial, as it is subject to many problems that can make it inefficient, unrepresentative, and allow some proposals to be favored over others. Change the ballot, and you change the voting results.

Voting can be grouped into two main categories, referendum, one question (or one face to face), three possible answers, for (or choice n°1), against (or choice n°2), or blank. And the “multiple possibility” votes, for example during the election of a candidate, of a proposal, among more than two possible choices.

Referendum and Quorum

For referendums, there is no need to reinvent the wheel, the system is not fallible (if one does not take into account potential problems related to the distribution of voting power), if it incorporates what is called a quorum so that the vote is not biased by the rate of participation. A quorum can be expressed as a minimum percentage of participation below which the vote will not be considered valid because it is not representative of all potential voters. The 51% quorum is the most used, and can introduce in some cases, the concept of majority threshold, I explain myself:

If a quorum is met in a vote, the majority can sometimes be calculated not on the basis of the voters present, but on the basis of all potential voters, so if the 51% quorum is just met, for the proposal to be accepted, the majority is set at 98%. Thus, the vote cannot be challenged by parties who did not participate in the vote, because even if they were present, the majority would have been reached anyway. The Quorum with majority threshold is always representative of all potential voters, but it also gives power to abstention, because if it exceeds 50%, the vote cannot take place.

Also, the Quorum must be chosen carefully so as not to present a risk of immobilizing the DAO if, for example, a large part of the community becomes inactive on it. It can also be used to limit the centralization of decisions by setting a limit not on voting power, but on the number of participants. Thus, if the community realizes that decisions are centralized around a majority held by too small a share of total users with common interests unfavorable to the interest of the group, it can decide to abstain in order to block decisions and put pressure until a reform of the voting power is proposed.

The referendum can be improved, however, thanks to a system that I will detail below called Mehestan voting. This allows us to indicate the intensity of our preferences for one option over another, making our words more measured, less binary. It can also allow us to detail several intrinsic components of the proposals, for example for the MEX 2.0 vote, we could have detailed all these major characteristics. This allows us to show that although we want MEX 2.0, there is one feature that we do not want to see implemented in its currently proposed state.

Multiple Possibility” Voting

For multiple possibility voting, it is a little more complicated, because there is an almost infinite number of possible ballots depending on what is to be elected. There are two main types of ballots, themselves infinitely variable:

- Majority vote: To elect a candidate/proposal, can be one or more rounds, absolute or relative majority

- Proportional voting: When you have to distribute a quantity to several candidates, each candidate earns a share of that quantity according to the proportion of the vote they received

Majority votes have two major problems to face, the dilemma of the useful vote, and the dependence on irrelevant alternatives.

The dependence on irrelevant alternatives is the dependence of the voting result on the addition or removal of one or more participants/choices. To help you visualize this problem, I’ll be forced to use a political analogy, don’t blame me for that:

You have 3 candidates running in an election, candidate A is politically right/conservative oriented and candidates B and C, politically left/progressive oriented. Just over a third of the voters are right wing, and just under two-thirds are left wing. The result of the vote is as follows:

- Candidate A 37%

- Candidate B 33%

- Candidate C 30%

Despite the fact that one of the two ideologies has a large majority among the voters, the presence of 2 candidates on the left dilutes the votes of this majority so that the less popular ideology wins. Without the participation of candidate C, candidate B would have won by a wide margin, so the result is said to be dependent on an irrelevant alternative, the one of candidate C.

As for the useful vote, it follows directly from the problem mentioned above. Voters who are aware of this problem will therefore vote not for the choice or the candidate that suits them best, but will vote for the candidate who has the best chance of defeating the candidate or the proposal that they absolutely do not want to see win. Voters no longer vote by preference, but vote against a candidate/proposal.

This is a huge problem in our current democracy, because it sacrifices the political plurality and the representativeness of the vote by favoring bipartism, the political bipolarization of the voters and can lead an unpopular candidate to win the elections, because it is the “lesser evil” in a way. End of the political aside, let’s go back to neutrality.

These issues have been more broadly formalized in a mathematical theorem by philosopher Allan Gibbard and economist Mark Satterthwaite, demonstrating that the only unanimous and independent vote to irrelevant alternatives is dictatorship.

Not very cheerful for our ideals of decentralization.

These two major problems are amplified by the ballots commonly used today, which is why a DAO must choose a ballot that avoids them as much as possible, because there are some!

Alternatives of choice are the Condorcet ballot and the Mehestan ballot.

The Condorcet ballot

Condorcet starts from a fundamental principle: If an alternative is preferred to any other by a majority, then it must be elected.

This principle seems trivial, but we have seen in the previous examples that its application is much more complex than we think.

Graph of Condorcet

In a Condorcet vote, the proposition is elected if and only if it is the Condorcet winner, i.e. which one is preferred to any other proposition if they face each other in duel. To do this, there is no need to multiply the votes, the voter ranks the propositions by order of preference. A very important feature to remember is that this ballot remains valid when a voter provides an incomplete ranking or when he is not able to favor one candidate over another. This allows for a right to be ignorant without biasing the results of the ballot, so you don’t have to be omniscient about the subject of the vote.

But you may have seen it coming, this system is subject to a paradox, called Condorcet’s paradox. It is possible that none of the propositions wins over the others, resulting from a cyclic graph where each proposition defeats two other propositions and loses against a third. A solution exists to this paradox which remains unlikely, but involves the application of a non-deterministic decision with a random draw of the winning proposition called a randomized Condorcet ballot, but I leave this subject for another time.

In the case of a Condorcet equality, we could leave the choice to the Core Team or to a community of elected experts, which seems to me acceptable, and you?

But even if the Condorcet ballot has very enviable characteristics and would be a very good candidate when we have to vote between several proposals, it is not adapted when the number of candidates is very large, for example in our case, to elect or rank the best proposals among dozens or even hundreds of proposals made by the community in view of a real collaborative governance. For this kind of decision, a ballot has been developed by mathematicians from EPFL, the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, called the Mehestan ballot.

The Mehestan Ballot

The inner workings of this ballot are far too complicated for me to present here and are probably beyond my knowledge, but I can show you how it works from the voter’s perspective.

On this site, which I strongly encourage you to visit and even use in your quest for knowledge on the net, the Mehestan ballot is applied in order to decide in a collaborative way which YouTube videos to recommend. It’s a kind of collaborative and alternative algorithm to the YouTube one that can be implemented on the platform via a plug-in.

The voter does not choose qualitatively between one video or another (either he votes for video A or video B), but will express the intensity of his preferences quantitatively. He can also choose to make his judgment more precise by choosing from a panel of nine characteristics. This system allows for a much less arbitrary and Manichean rating and ranking, while allowing everyone to express the complexity of their opinions.

I think this is the ballot that should be chosen for the community proposals, it requires more commitment than the traditional ballots, but allows to use the full potential of collaborative governance. It could also be very useful for the referendum vote, as part of the vote about the move to MEX 2.0, it would have allowed the Core Team to have feedback and a more representative vote of the overall opinions on each major component of the update.

Finally about proportional voting, it does not have all the problems mentioned above as it is used to distribute a quantity according to candidates, for example, seats in parliament according to several political parties. Its use should be more anecdotal in a DAO, but could for example allow farming rewards to be distributed according to several pools of liquidity, with each voter being able to divide his voting power to elect his preferred mix.

The ballots chosen for each type of decision as well as the distribution of voting power will be the foundations of a fair and representative community governance in order to maximize value creation and avoid vote manipulation. But how to mix the two to build the ideal DAO? This is where we need to look at game theory.

7/ Governance according to the Game Theory

Game theory is a concept that is widely used in blockchain, whether to ensure the security of a network, favor its decentralization or build micro-economies. Game theory is a formalization of the strategic interactions between the different stakeholders of this game, called “players”. It establishes a theoretical framework to model how humans or entities would behave in different strategic economic or sociological games in order to maximize their gains.

There are five principles derived from game theory that will interest us here:

- The fundamental principle of politics of De Mesquita: An entity or a man in power is neither benevolent nor malicious, neither charitable nor Machiavellian, all he wants is to stay in power, so all his actions will be dictated by this will, whether they are good or bad for the entities he governs.

- A derivation of Murphy’s Law stated by David Freeman: Any system that can be manipulated, will be manipulated and at the worst possible time.

- Nash equilibrium: Assuming that most games are not zero-sum, each player reacts to the actions of others in a way that is optimal for him and according to him.

- The tragedy of the commons: Occurs when competing for access to a limited good, creating conflicts between individual and group interest, resulting in a lose-lose situation for all users.

- Price of Anarchy and Braess’ Paradox: A feature that can be individually beneficial to all, can be very detrimental to the interest of the group.

The fundamental principle of the policy

It tells us that the 34 Whales who now have the majority will act in such a way as to keep it, whether their actions are favorable or unfavorable to the group’s interest. Everything depends on the incentives that push them to carry out such and such actions. This is why, if the change in the function of voting power is to be made through governance and not through a centralized choice by the Core Team, the proposals will have to include incentives that will push the Whales to share their voting power more equitably.

Murphy’s Law

One of the fundamental tenets of a DAO is that none of its components should be manipulable, even under unlikely circumstances, as this is bound to happen at some point. This would allow malicious entities to take control, so it is crucial to further decentralize the governance of the xExchange even though the Core Team will undoubtedly have veto power over any proposals from the community. The 34 Whales could band together to push proposals from which they alone would benefit.

Nash equilibrium, theorized by John Nash.

Nash understood that most strategic interactions or games are not zero-sum. Nash equilibrium are the results of the combinations of player interactions that are optimal for them and according to them. Understand that each player will play the strategy that maximizes his chances of winning according to the different possible choices of his opponents, making his choice non-regrettable once the results are known. Most “games” are not zero-sum, so there are outcomes that are win-win or lose-lose as in the prisoner’s dilemma. A small example:

Table of interactions and results between community and Core Team

Why is it in the Core Team’s interest to share the governance of the xExchange with the community?

If we schematize the different possible actions of the community and the Core Team as well as the mutual result of these interactions, we notice that only the implementation of governance if and only if it is requested by the community is a win-win result for everyone. It is said to be a Nash equilibrium because knowing the interactions of the Core Team for the community and vice versa, each of the two players could not make a better choice for them and according to them:

- If the community does not press the Core Team for access to more governance or does not present the need for it, the Core Team will be better off not giving it to them because the community will be indifferent, doing so would be an unnecessary loss.

- If the Core Team chooses not to give governance to the community, even though it would be a win situation if the community does not present a need for it, it could put itself in a very bad position if the community strongly demands it, and could lose their users.

- If the community demands governance, it will gain a lot of power if the Core Team agrees or will be greatly disappointed but can always change ecosystems.

- Finally, if the core team implements governance, even if it would lose out if the community is rather indifferent to this feature, it will delight the community if that is their wish and will allow them to consolidate their relationship with them while bringing added value to the ecosystem.

Each “player” considering all the possibilities of action of the other “player” according to their own possible choices, the one that maximizes their gain is the demand of governance for the community and the implementation of governance by the team.

This vision of interactions between “players” should inspire us to build a governance that favors win-win outcomes between the Whales and the Community, especially when it comes to decentralizing voting power. If changes to increase this decentralization are to be made through voting — which today would be one-way — we must be able to push the Whales to vote in favor of it by creating incentives that will bring this result to be a win-win Nash equilibrium.

The tragedy of the commons

Previously, we considered a game between only two players, but Nash equilibrium can be generalized to an entire community. When you act immorally in society, you are acting as what is called a “Free-Rider. You are playing a lose-lose Nash equilibrium, and relying on others not to play that equilibrium in order to come out “winner”. For example, in Launchpad, some people decide to act immorally by participating with multiple accounts, hoping that the majority will not imitate them in order to increase their chances of winning tickets. As you can see, it’s a vicious circle that pushes everyone to “cheat” to the detriment of the group, this is what we call the tragedy of the commons.

This is why we need to develop a system that punishes Free-Riders in order to break this loop that pushes to individualism. A more utilitarian vision but not necessarily incompatible with the libertarian or even anarchic vision of cryptos.

The Price of Anarchy and Braess’ Paradox

To illustrate the so-called price of anarchy, consider Braess’ paradox.

Graph of the Braess paradox

There are two roads to go from a city to the beach. Each road is equivalent in travel time, with a portion of highway of 45 min and a mountain road of 5 min but whose travel time is strongly impacted by the number of cars traveling it. The intersections between the highways and mountain roads are marked by two points A and B.

The city is considering opening a road connecting the entrances and exits of highways A and B. This seems to be a good idea because it will open a new route from the big city to the beach in 25 minutes. Therefore, all users should stop taking the highway sections and use only the small mountain roads.

However, these two roads are not able to accommodate all the motorists in the network, get congested easily, and now both take 25 min to travel.

By choosing the optimal route for them and according to them, the strategy of each motorist leads the whole network to be congested, and they now take 1h05 to go to the beach against 45min before the road was built. A decision that favors individual interest can be very detrimental to the group’s interest and the overall performance of the network because it causes users to “play” a lose-lose Nash equilibrium. We can also see the paradox in the opposite direction, suppressing a freedom, a feature that seems beneficial to you, can be beneficial to you and to the whole community.

This is an important paradox to keep in mind when making voting proposals, in order to avoid submitting proposals that will seem individually beneficial to each voter, but detrimental to the DEX and the community as a whole.

Tweet Share

You can check if you are not dealing with a scam

Check now

@elrondwiki.elrond

@elrondwiki.elrond